My colleague, Shannon Ang, and I have set up a research centre at Nanyang Technological University (NTU). The Centre for the Study of Social Inequality (CSSI) aims to:

(1) promote and enhance multi-disciplinary understandings of inequality’s various forms and dynamics;

(2) nurture public social science–attentive to the concerns of ordinary members of society, deliberate in making links between theoretical knowledge and practical solutions, and committed to making academic knowledge accessible to a broad public.

More about our mission here, and how the Centre came about here.

It is early days and we have much to do. We’ve begun the work of building up networks amongst scholars, across various universities in Singapore and from multiple disciplines; we’re pleased that many colleagues have agreed to be centre Associates. We aim to support younger scholars interested in pursuing the study of inequality in Singapore and are also happy to have granted our first Junior Visiting Fellowship. In May 2025, we will co-host the Population Association of Singapore’s (PAS) Annual Meeting, with the theme of “Demography and Inequality: Intersecting Paths.”

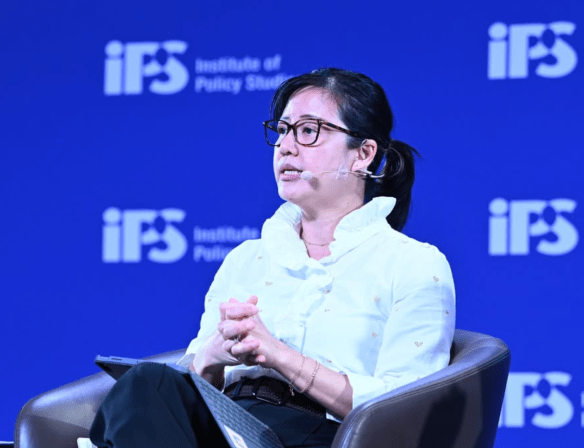

Networking lunch with some Advisory Board members and Associates, February 2025

The founding of a centre for the study of social inequality, unimaginable just a few years ago, speaks to changes that have already occurred in our society’s collective commitment to inequality as a problem. We believe research and knowledge are crucial for further generating ideas for solutions and for continuing to energise society’s collective response to an urgent social problem. We hope colleagues, collaborators, allies, and fellow members of Singapore society will agree.